The hardest part of design is knowing when to stop

If you haven’t worked on too many projects, it can be easy to treat your work like a new born baby. You want to protect it, and make it look amazing. The problem with over managing your work is that it could lead to over refinement or the fear of making changes when needed. It clouds your judgement in that the design is part of the problem solving process and will change depending on the situation. The difference is that some changes are needed to address the problem, while others are not necessarily critical in addressing the problem.

A design is finished when you set actionable constraints or scope. Once you validate your design is needed and works well, then it might make sense to go back to it and iterate, but otherwise setting constraints and scoping your design to effectively address a problem and users is good enough. That is usually the hardest part.

Here are some specific ways to help dictate when your design is finished:

If it addresses the core problem and user needs

For more context, read What Makes a Good Design Project?

How can you know whether or not you are solving for the right problem in your design process? You can base it on user testing or evaluate each part of your outcome, and ask if it addresses a core need(s) for the user. If everything connects, from initial explorations to the final outcome, you are “finished”. If the outcome or visuals don’t really communicate the problem or the user, then you should go back and refine. How you could go about doing that is through story mapping.

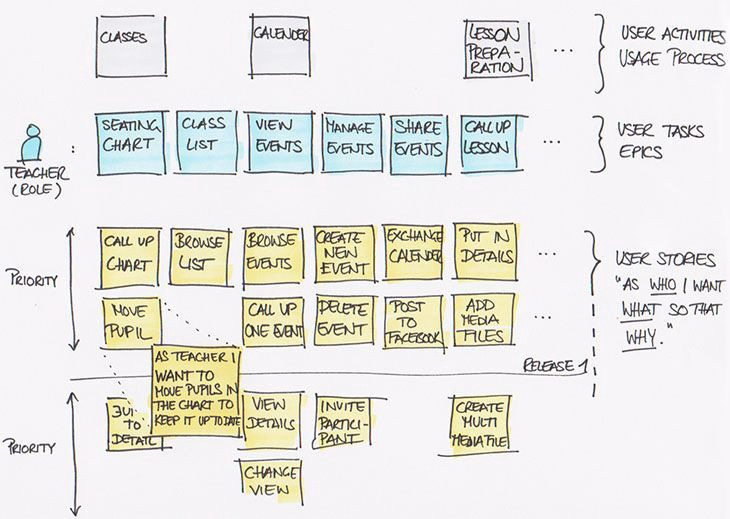

An example of a story map

Story mapping allows you to visually map out how your solution would work in your user’s journey and help you make visual decisions that connect to your research and your goals. It can help you prioritize what you need to work on or if you are leaving anything out that is crucial in the user’s journey.

Here is an example on how to structure a map:

1. Title, goal, user (role)

2. First row is what the user needs in order to achieve their goal (user activities)

3. Second row are the tasks they need to do in order to achieve their goal (user tasks)

4. Third row and forth rows are the specific stories, the actions they can do using your solution to achieve the tasks. Match them under the tasks. Stack them based on what you are measuring (i.e. priority, does it best address the problem at this moment, etc.). You can also add on to the stories with specific design patterns you could use for the actions.

If you have little to no time left because of a deadline

Depending on how far you are in your project, prioritizing what is essential in your outcome should help you get into the mindset of knowing when your project is done.

Don’t place too much emphasis on a project once it meets a deadline and solves the essential user need. This especially applies at work, where your work is constantly going to change, be ripped apart, and you will continue to get more work.

Once a design is finished, you can always go back to a design, whether there’s an urgency to refine, add onto it for accurate documentation, or for portfolio and interview purposes.

If it meets minimum* product requirements

At an organization, we base the progress of our work on OKRs (objectives and key results). P0 or P1 are essential and are part of the minimum viable product experience. These often dictate a launch, which sometimes co-relates with product completion at a certain time until follow up work is required.

P2, P3 and beyond things are nice to have, but aren’t needed. P0 and P1 things are crucial to the function of the product, and the user experience. Once you meet those, you don’t need to worry about the rest too much because the chances are that the features are not scoped out. You can help scope it out with your PM, but once the core product is done and it addresses the main problem, then the rest isn’t crucial to the product functioning unless there is more time to work on it before another project comes along.

Ask if the product is able to function with or without x feature? If it is able to function without it, you are done (for now).

As much as I would like to continue building and scaling a product, once it’s launched, the rest is typically maintenance until new things need to be added based on users and metrics, or if we have the resources needed to move forward. With that in mind, I would try to balance time on other projects that have more aggressive timeline. I would discourage doing exploratory work for a launched project with P2 and P3+ OKRs unless it’s needed to progress right away, you have the bandwidth to do so, and it will be implemented ASAP.

Ending notes

Remember that there is a thin line between refinement and using that to dictate when your project isn’t done. Over designing can hinder the overall process if you don’t think about how refining it will help the user or address the problem. If there is a good reason to refine, such as improving part of the user’s journey, then do it. Otherwise, once a design is finished based on deadlines, or if you have other projects to work on, then you are mostly done. This doesn’t consider the fact that, in an organization, metrics after a design might require you to look back on your design and work on it, but the chances of completely redoing it are slim, especially if your organization goes through a multitude of review processes.

Follow me on Twitter to keep up with updates!

Check out my Skillshare Course on UX research and learn something new!

To help you get started on owning your design career, here are some amazing tools from Rookieup, a site I used to get mentorship from senior designers.

Links to some other cool reads: